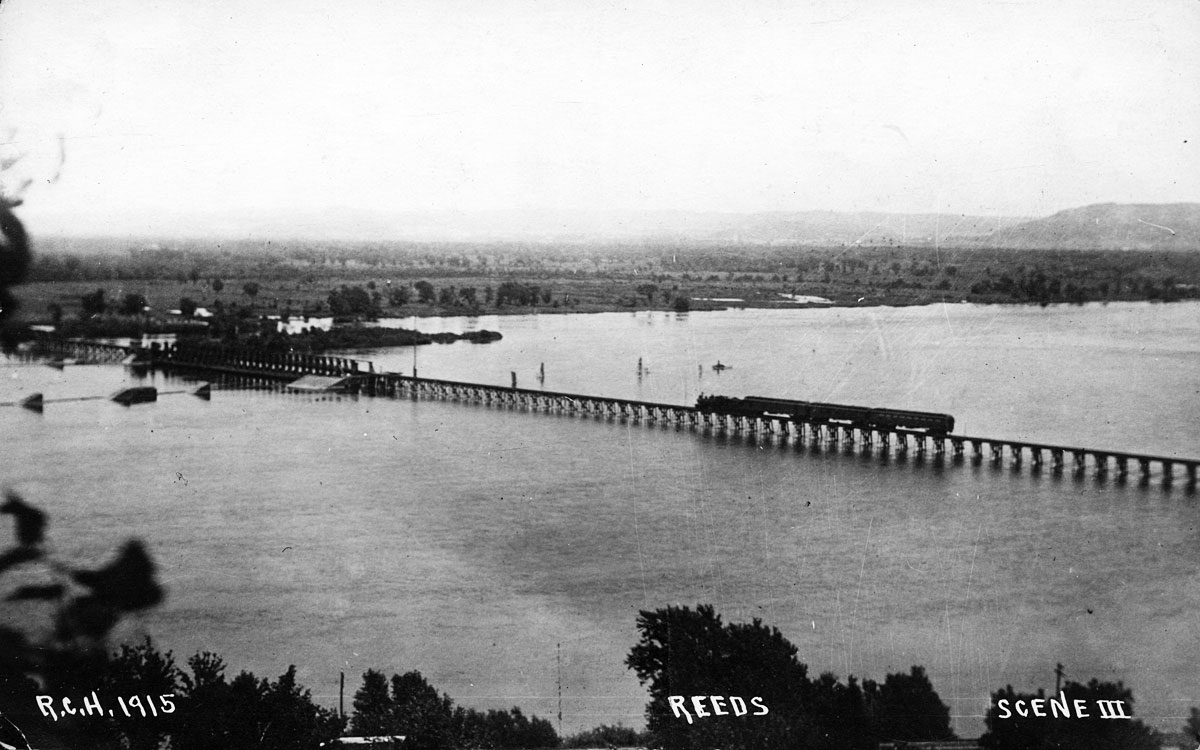

Chippewa Valley and Superior Railway steam train crossing the Mississippi River from Reeds Landing, Minnesota. Courtesy Bob Nihart and the Reads Landing Brewing Co.

The Chippewa Valley Line

Map of the Milwaukee Road. The Chippewa Valley Line is in red. Courtesy of Eau Claire Leader-Telegram

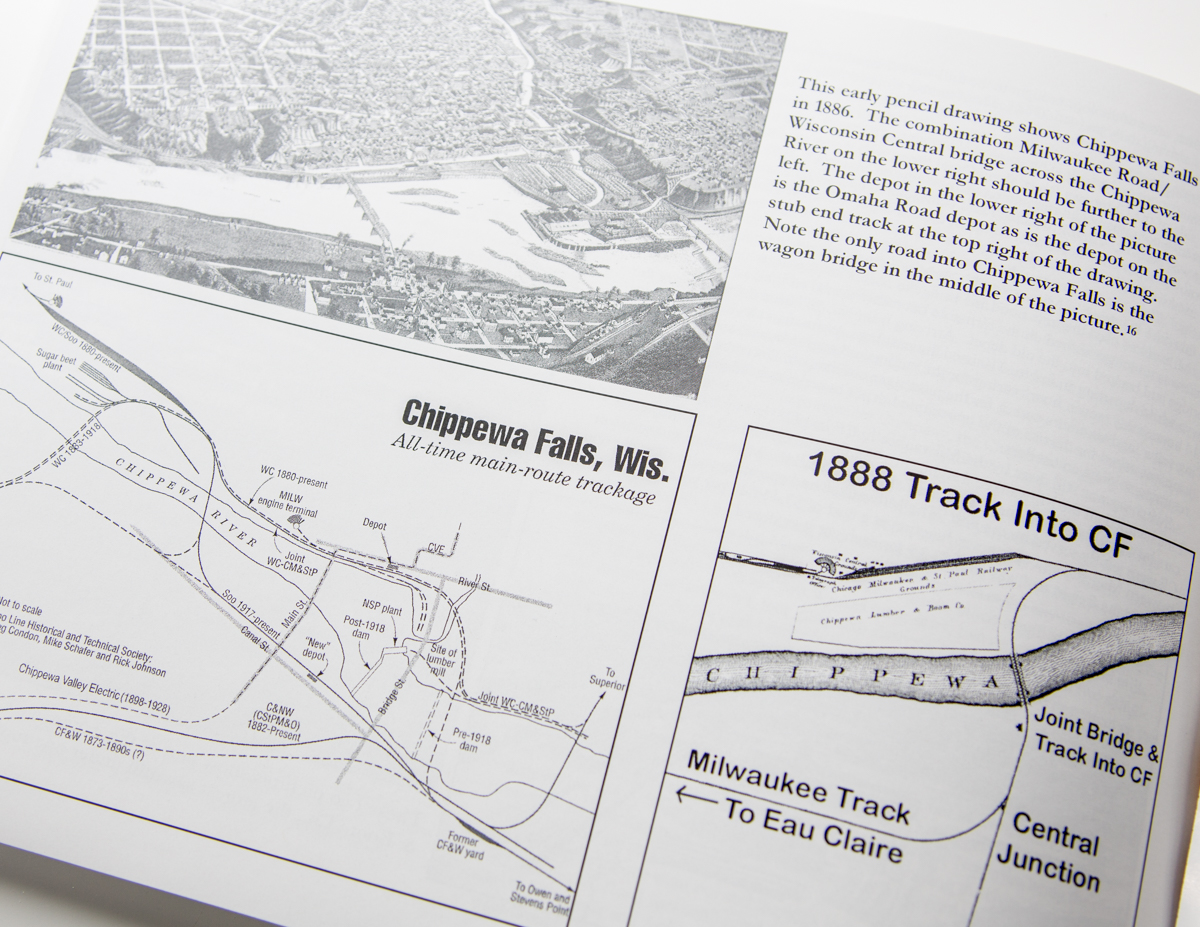

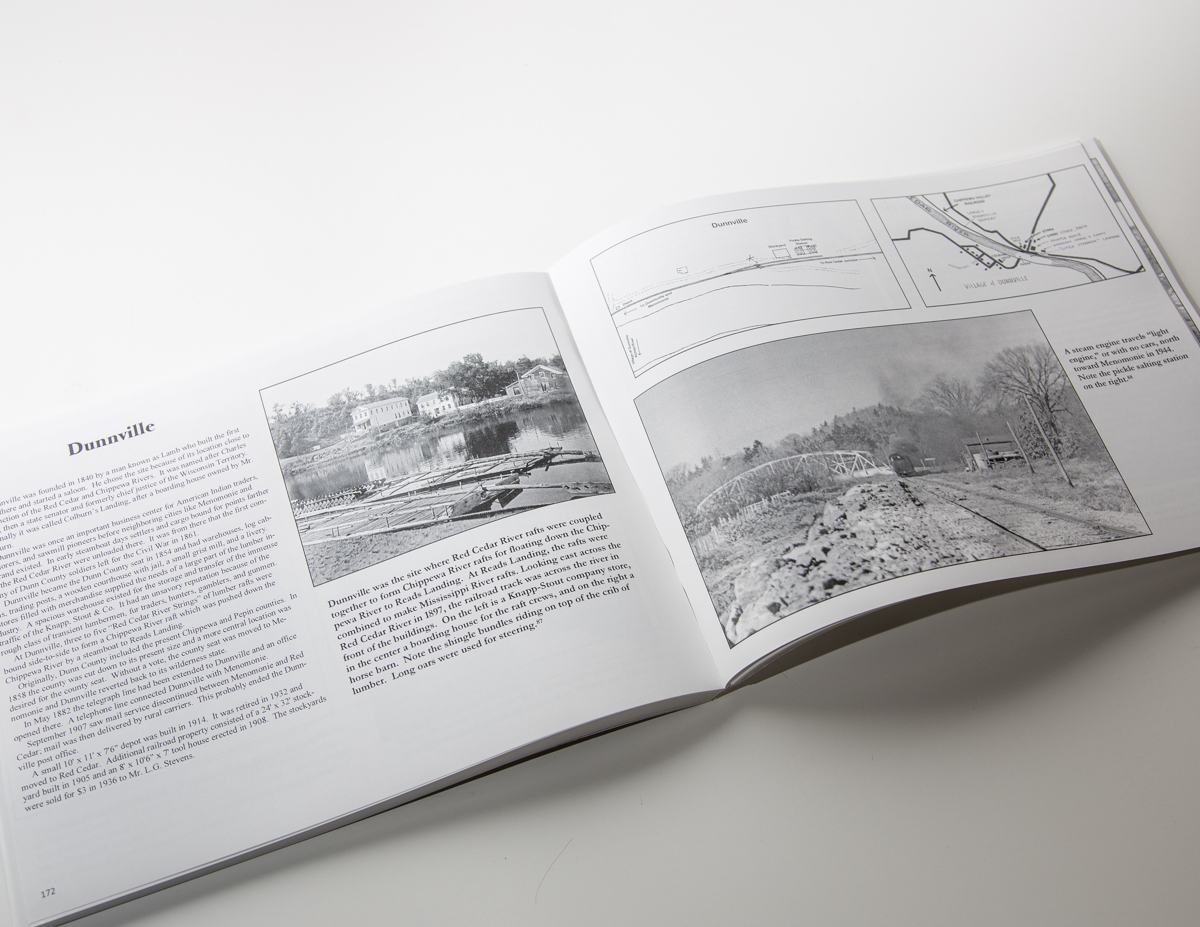

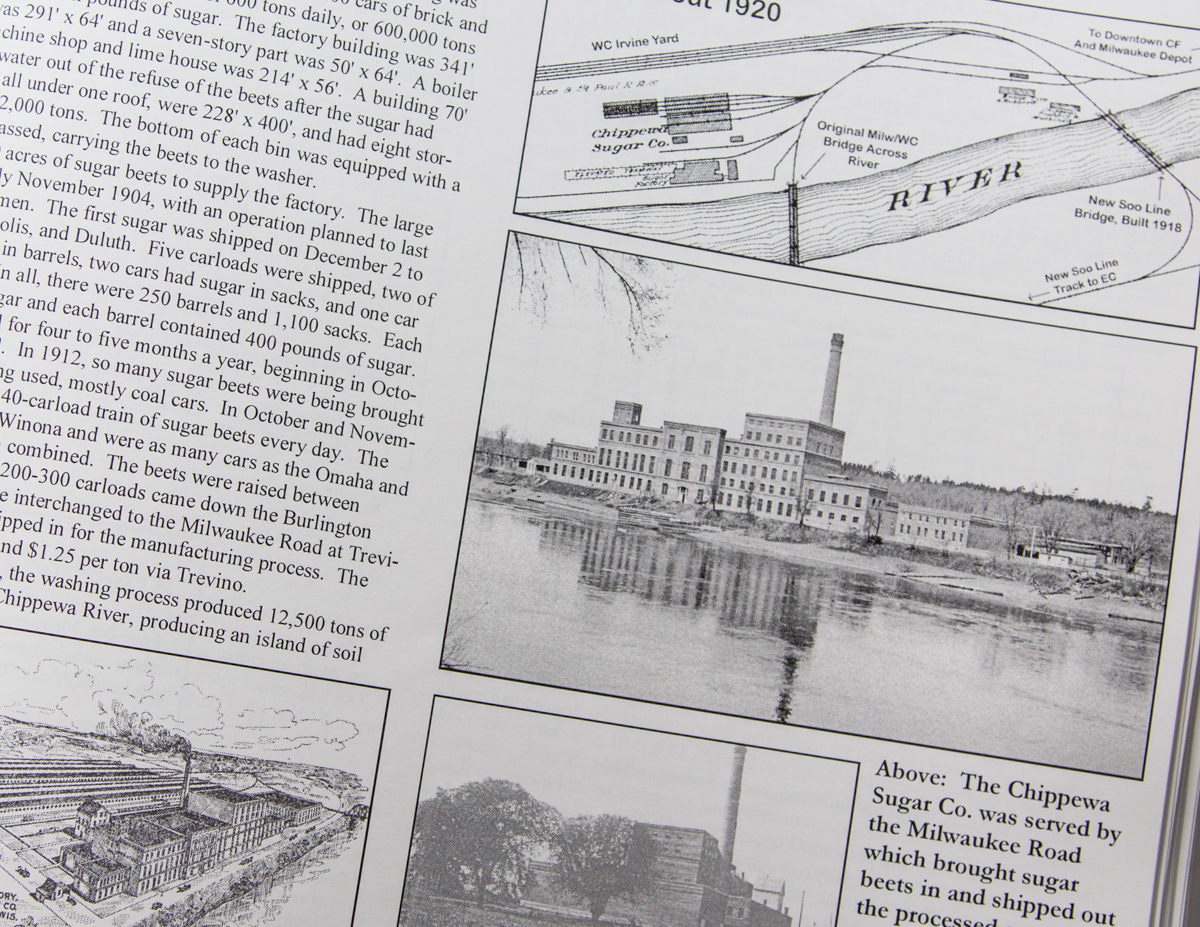

Below is select text about the Chippewa Valley and Superior Railway Company’s floating pontoon bridge from the book, The Chippewa Valley Line – The History of the Chippewa Valley and Superior Railway by Arlyn Colby. The book is about the railroad line that was built to serve the logging industry and communities along the Chippewa River and Red Cedar River. The line ran from near Wabasha, Minnesota across the Mississippi River and up the Chippewa River in Wisconsin to Eau Claire and Chippewa Falls. The line branched off north of Durand at the confluence of the Red Cedar River and continued up the Red Cedar to Menomonie and Cedar Falls. This line would become part of the Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul and Pacific Railroad, known as the The Milwaukee Road. The book includes more images and history about the pontoon bridge across the Mississippi River than is included here.

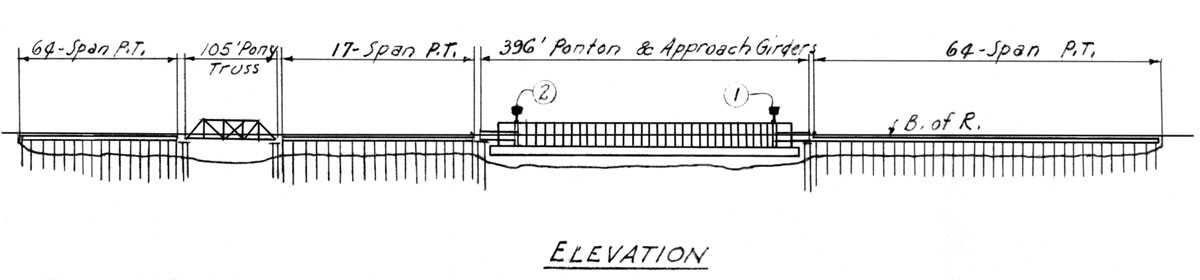

Reeds Landing Pontoon Bridge blue print. Courtesy of Ted Schnepf

Pontoon Railroad Bridge

Building the Chippewa Valley Line required a crossing over the Mississippi River, the “Father of Waters.” This mighty river near Wabasha is approximately 3,000 feet wide and required an extensive bridge system for crossing.

The Wabasha Herald, in July 1881, quoted Chippewa Valley and Superior Railway Company President Easton as saying the railroad would cross the river at Wabasha, at a place called the Point. The people of both Reads Landing and Wabasha were interested in their location as the southern terminus of the line. Predictions were that if the line was built on the west side of the Chippewa River that the line would connect at Reads Landing, and if built on the east side of the river, it would be built to Wabasha. Even Winona tried to get into the act by offering a $100,000 bonus to have the railroad cross at its location. However, that proposition was likely never seriously considered because it would have required building two bridges and a new rail line on the east side of the river to a point opposite Winona.

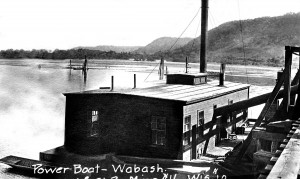

Pontoon Bridge Power Boat used to swing bridge open and closed. Wabasha, Minnesota. Courtesy of Fred Hoeser

On March 14, 1882, the 47th Congress, 1st Session, by House Bill H.R. 4440, granted the CV&S Railway Company “permission to establish a railway bridge across the Mississippi River extending from a point between Wabasha and Reed’s Landing in Minnesota to a point below the mouth of the Chippewa River in Wisconsin.” Rafting and steamboat interests vigorously complained about the possible site of Reads Landing for the bridge. They claimed it would be a serious obstacle to navigation and wanted it located between Island No. 29, or Drury’s Island, and Wabasha. Other drawbacks to that location were costly and difficult approaches to the bridge from both sides of the river, an increased length of track to construct, and a possible future change in the channel. However, the railroad wanted the Reads Landing location because the channel there had been unchanged for 25 years and the government dams that had recently been made near there tended to hold the channel where it was. An additional reason to have the crossing at Reads Landing was in case the right to construct the bridge could not be obtained, the railroad would not be delayed in its construction or operation because a ferry transfer could be established there.

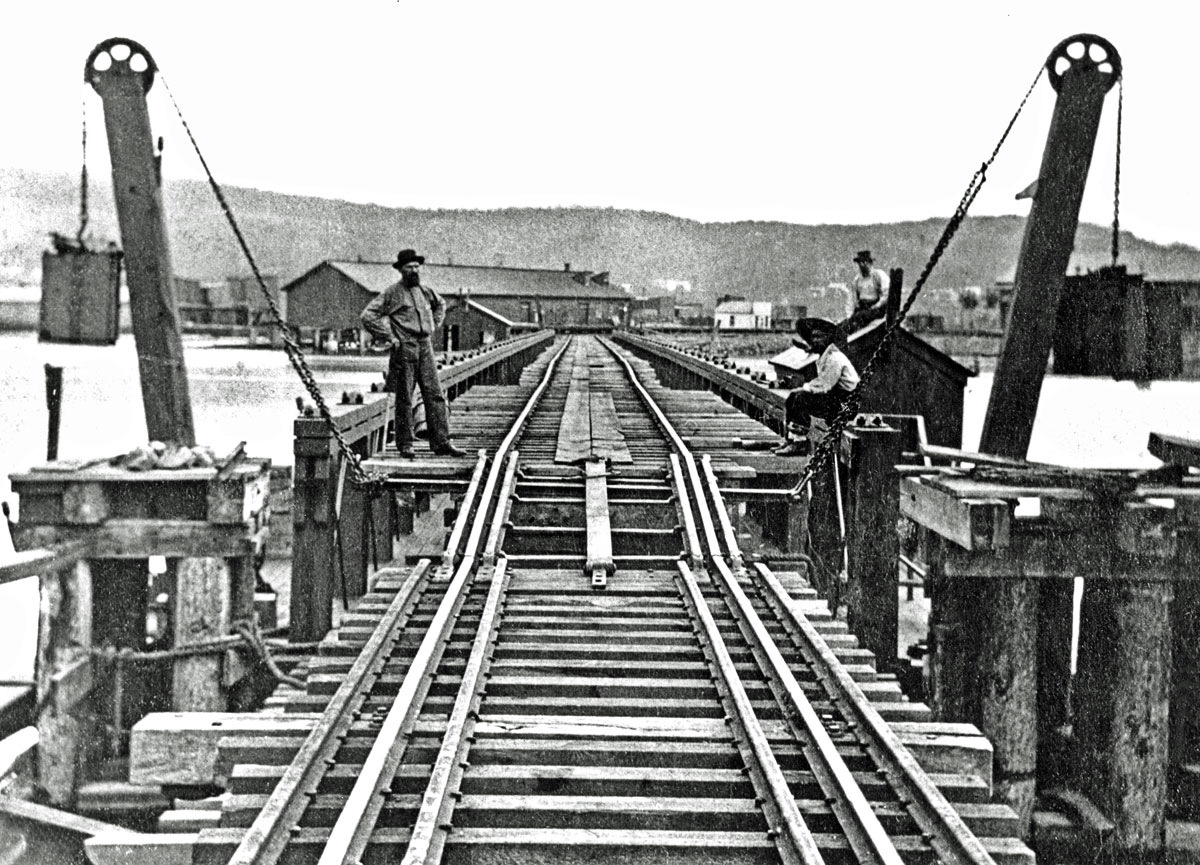

John Lawler Sr. was selected as the contractor for the bridge. Lawler’s railroad river crossing concept was to traverse a river on pile trestles except for a pontoon section. The pontoon would be a big barge, hinged to a permanent piling at one end, called a hinge pier. The hinge could move up or down on its pin, adjusting to changes in the river’s depth. On the open end of the pontoon there would be a steam power house with an engine and winding drum. A chain was attached to an anchor pile up stream, run across the drum and then to another anchor pile downstream and at right angles to the bridge in closed position. When the bridge needed to be opened for river traffic, the chain drum pulled the free end around against the downstream anchor pile. When closed, the free end was secured to the trestle piling.

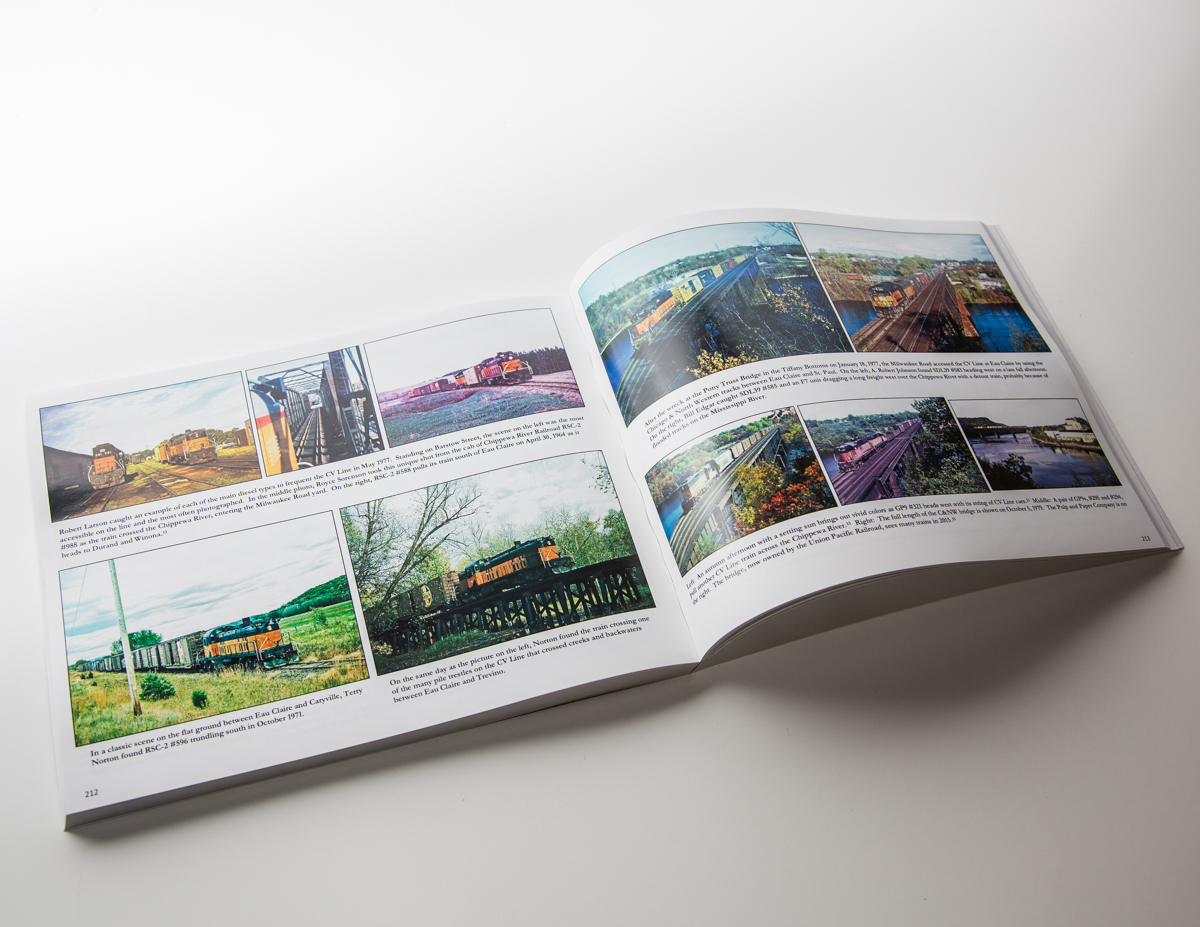

Milwaukee Road on the Chippewa Valley Line south of Durand, Wisconsin. Courtesy of Terry Norton

Bridge Operations

Due to extreme changes in the water level of the river, the height of the pontoon had to be adjusted. At each end of the pontoon there was a long apron and a short apron. The long apron was pivoted on the trestle a distance from the pontoon. The outer end could be raised or lowered to correspond with the level of the pontoon. This adjusting was made by using jacks and blocks. When the river rose, men used the jacks to lower the track, inches at a time. When the water level dropped, the action was reversed and the tracks were raised. Often when the river level fluctuated a lot in the spring, the crews would work around the clock. The short apron was used to allow for the pontoon “sinking” under the weight of a train. When a train was on the pontoon, it would be nearly level. The trick then about the pontoon was to keep the floating rails, no matter how high or low the river was, at the same level as the tracks, which extend to the pontoon from either shore on pile bridges. It was managed by pulling out blocks or putting them back in again. The pontoon had two floors, one in the hull, the other up above with the railroad tracks on it. The upper floor was supported from the first floor on either side by 19 columns of nine inch movable blocks. When the river was rising, blocks were removed to correspond to the number of inches of rise. When the river was falling, the blocks were reinserted. The lower floor was thus allowed to raise and drop with the changing water level, while the upper floor with its tracks was held in the same position.

The outer end could be raised or lowered to correspond with the level of the pontoon. Often when the river level fluctuated a lot in the spring, the crews would work around the clock.

Although the pontoon was 400′ long, the river is nearly three miles wide including the sloughs on the east side, so long trestles formed the approaches. The overall length of the bridge system was 2,795.5 feet. The east approach consisted of 64 timber pile trestle spans for a distance of 1,011 feet. The west approach had 74 trestle spans for a distance of 1,050 feet. In addition to this, there were a 105-foot span pony truss allowing passage of small watercraft and two iron span girders.

The first passenger train, an excursion train with railroad officials, crossed the bridge on July 8 with six freight cars and two passenger coaches. On board were GM Merrill and other railroad officials. The trip to Eau Claire was a slow run, allowing the officials to closely inspect the line, in which they expressed great satisfaction. July 13 marked the beginning of regular service with a mixed train daily.

Train speed over the pontoon was limited to 6 MPH. A 1914 timetable listed the rule that “trains are required to stop within 400 feet of the pontoon and not exceed six miles per hour.”

Mississippi River pontoon bridge approach. Courtesy of Cecil Cook

Navigation

Lawler enumerated the advantages of this bridge: A floating structure would not interfere with the natural course of the river, the bridge would float any weight placed upon it, it would be cheap to build compared with other bridge structures, it could be completed in a relatively short time, and a wider channel could be maintained for passage of steamboats, logs, and lumber rafts. Raft pilots, though, were not enamored with the bridge because it would require fancy piloting to pass through the bridge successfully with their long tows of barges.

When navigation on the river ended for the winter, the pontoon was closed until navigation reopened in the spring. If the pontoon needed repairs during the winter, the railroad would drive a standard pile trestle in the pontoon area and float the pontoon to Wabasha. Before the navigation system resumed, the temporary pile trestle was removed and the pontoon floated back into position. If the pontoon remained on site during the winter, there was a crew assigned to chip ice and keep it free from ice buildup. They used steam from the boiler to help melt the ice. Frequently, ice flows caused problems for both the pontoon and the trestle, despite the placing of ice breakers up river.

Overlooking Reeds Landing, Minnesota and the railroad pontoon bridge across the Mississippi River. Courtesy of Fred Hoeser

Challenges

A pontoon bridge was very labor intensive and expensive to maintain. Three shifts of men each working eight hours a day manned the bridge. Besides the normal wear and tear, floods and ice damaged the bridge and trestle work frequently, even though the pontoon was protected by wooden ice breakers, huge wooden structures that projected out of the water to deflect ice. They had to be frequently rebuilt, so a pile-driver barge was always kept nearby. Even in the winter they required a crew who cut away ice and raised and lowered the deck as the river level fluctuated. There were also periods of extreme high water when the bridges were left open and could not be used by trains. Ice became an even bigger problem after ice breaking boats were used to open Lake Pepin, resulting in much bigger ice floes ramming the bridge.

Even though the pontoon was protected by wooden ice breakers, they had to be frequently rebuilt, so a pile-driver barge was always kept nearby.

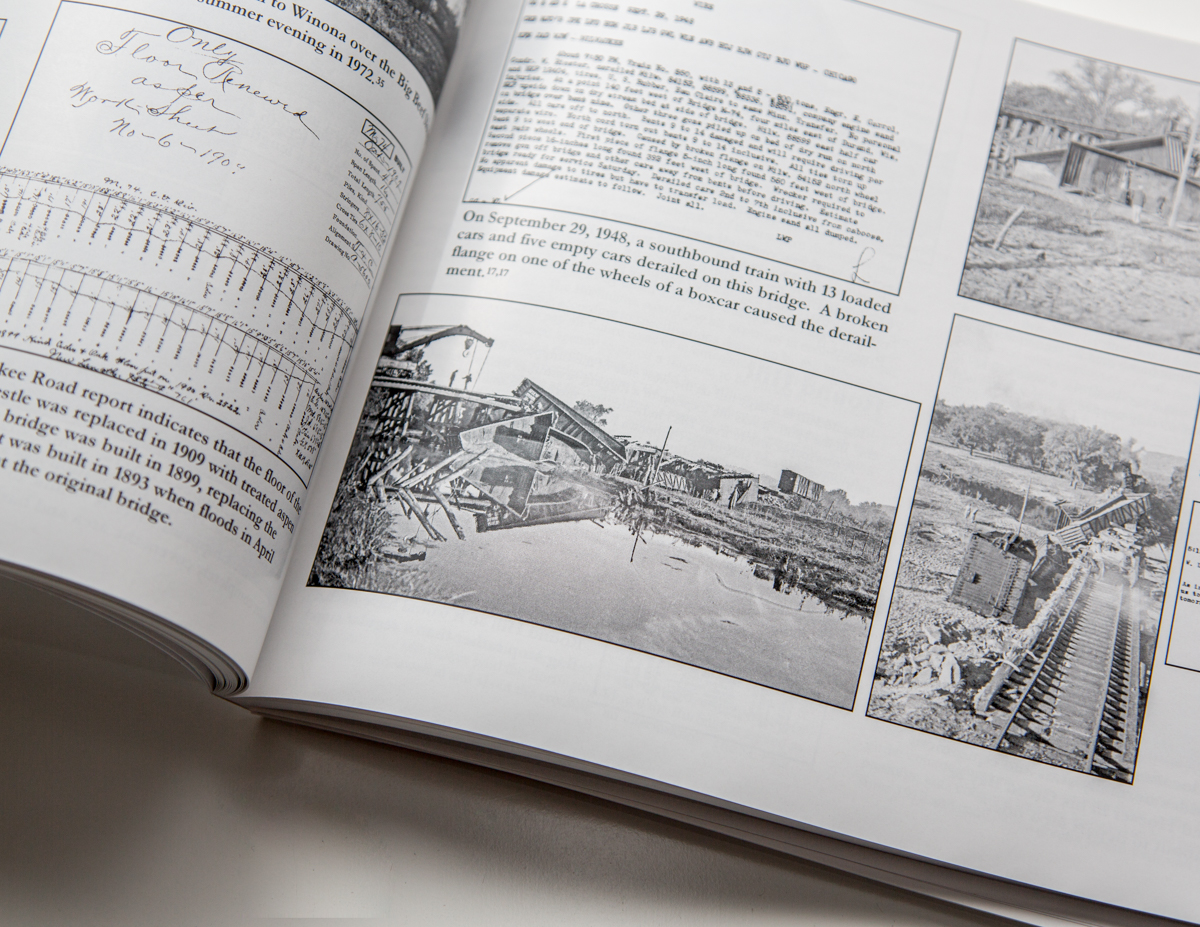

Low water in 1886 caused trouble for river traffic. Railroad Superintendent Lackey built a dam from the Minnesota shore to the lower side of the pontoon which gave the channel a depth of 30 feet, allowing even the largest boats to pass through the waterway. A flood in April 1888 “badly wrecked” the pontoon and it was out of service for weeks. In the meantime, passengers were ferried over the river to connect with waiting trains. Suspension of train traffic over the bridge because of ice occurred most years, most often due to failure to be able to close the bridge.

Logs being run down the river in May 1889 caused the pontoon to remain open and delayed trains. Disgusted train crews and passengers were transferred at the bridge on barges to cross the river. The May 17 report indicated 30 million feet of logs went out of the Chippewa River down the Mississippi into West Newton Slough.

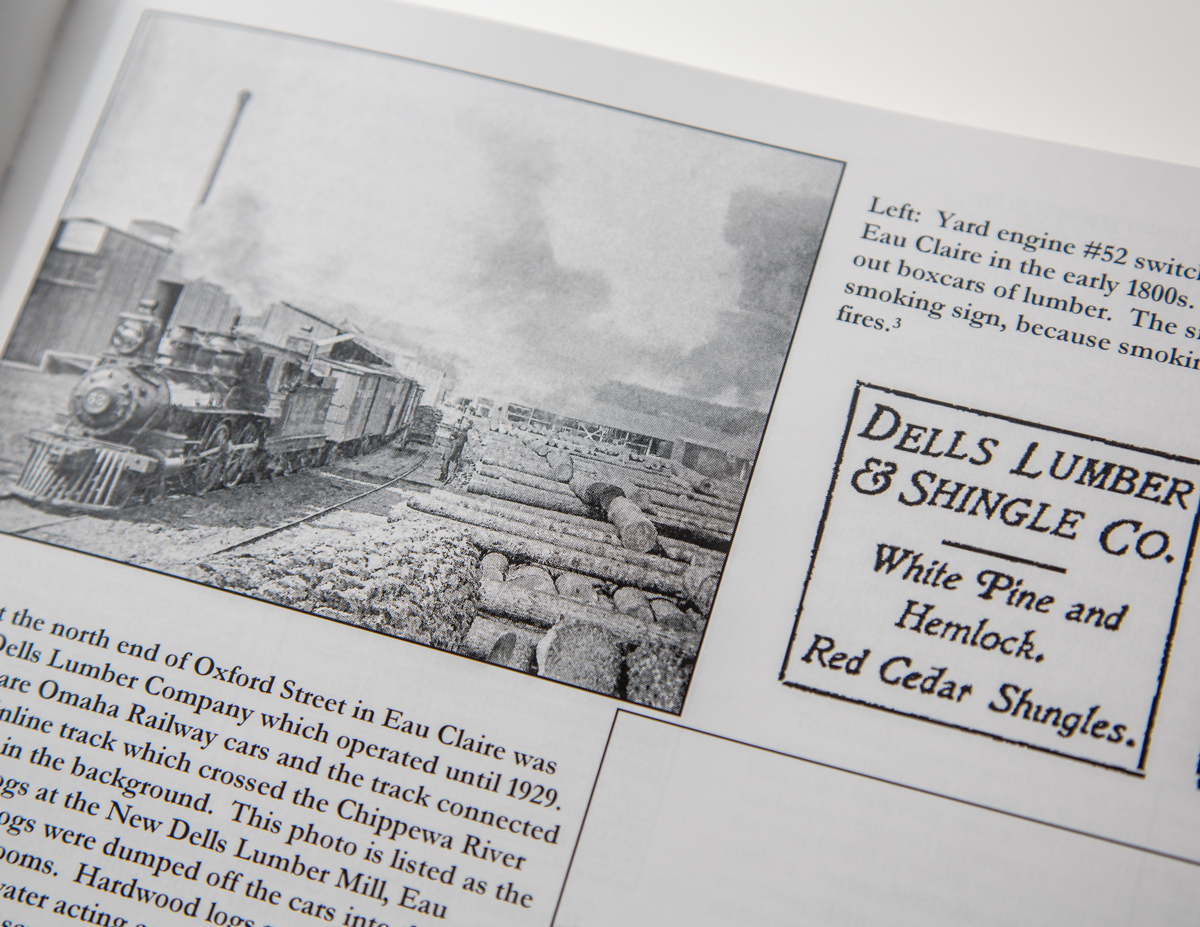

Knapp, Stout & Co. along the Red Cedar River in Menomonie, Wisconsin. Courtesy of UW-Stout Archives

Interesting Facts

- A serious wreck occurred in October 1904 when a freight train on the main line backed onto the Chippewa Valley line. Nine cars separated from the rest of the train, and owing to a down grade to the river, and since the pontoon was kept open unless a train was crossing, they ran off the trestle and into the water.

- More logs and lumber had passed through the CV Line bridge than through any other bridge in the country. But it had required three shifts of men working eight hours a day to keep it running and the long trestle leading to the channel and pontoon were very expensive to maintain, as were the ice breakers which had to be frequently rebuilt.

- Members of the Wisconsin National Guard were stationed at Trevino to guard the bridge over the Mississippi River during WWI. One member, Frank Neidbalski, was killed instantly when a speeder he was riding was struck by a Burlington Road passenger train.

- A section man fell off the pontoon on April 1, 1940 and drowned. The police department recommended better lighting on the pontoon so the company spent $462 on new oil lamps and a galvanized steel wire installed on the north and east ends to aid in safety. With the addition of electricity on the pontoon in 1941, electric lights replaced the oil lamps.

- In 1885 with the construction of the Chicago, Burlington & Northern (CB&N) between La Crosse and St. Paul, the pontoon bridge was used to transfer rail, ties and even locomotives to the railhead on the Wisconsin shore of the river. These shipments ran up the Milwaukee Road from La Crosse to Reads Landing where they crossed the river to reach the CB&N’s construction sites. Locomotive #4 made this journey in early November 1885, becoming the first in a large number of re-routings over the bridge.

The end of the pontoon came in 1951. For 69 years the pontoon bridge was a distinguishing feature of the Chippewa Valley Line, and one of those idiosyncrasies of the Milwaukee Road that makes it so fascinating to railfans and historians.

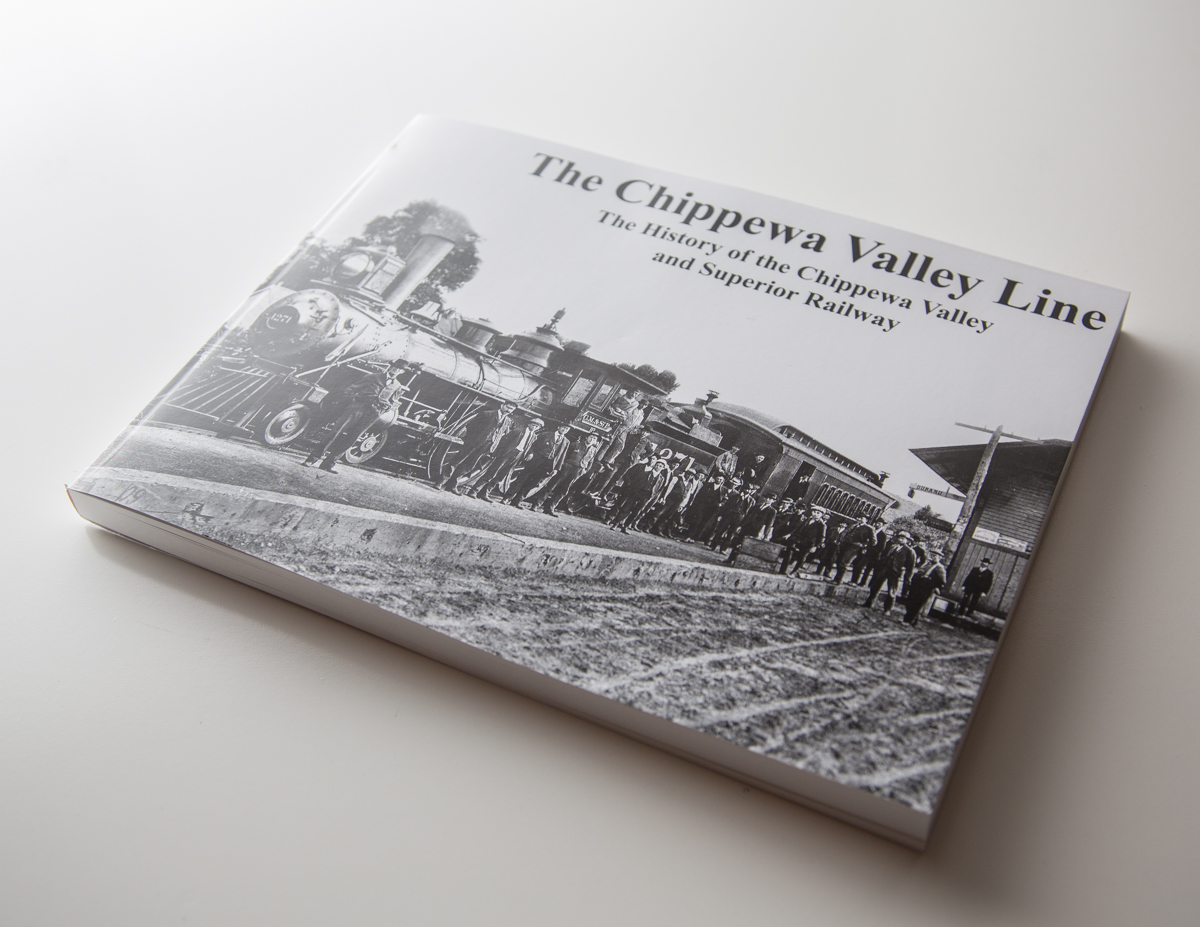

The Chippewa Valley Line – The History of the Chippewa Valley and Superior Railway

261 Pages – Perfect Bound or Spiral Bound – 8″ X 10 3/4″ – $30.00

You can order The Chippewa Valley Line by calling (715) 637-3928, or by email: barronrrbooks@yahoo.com

About the Author

Arlyn Colby, a retired math teacher from Barron, WI, is known to many railroad fans in the Indianhead Country as he has been involved in numerous railroad related events for years. He has taken on the important task of preserving railroad and community history of our region. Not an easy task. Several years of his life have been invested in accumulating the pictures, stories, and other details that he organized into the books, The Mondovi Line, The Blueberry Line, and The Chippewa Valley Line. His fourth book Omaha Branchlines In Northern Wisconsin is currently in progress.

Like and Share with your friends and family!

John Gruber

I have a sidebar, Milwaukee Road’s Pontoon Bridges, on pages 140-141 of North American Railroad Bridges (2007) by Brian Solomon. It features a Milwaukee SD9 with train on the pontoon bridge between Prairie du Chien, Wis., and Marquette, Iowa.