Tolland, Colorado

History of the Moffat Road

In the 1800’s, Colorado was pretty much a “gold” mine for settlers traveling west. The city of Denver was bypassed by the Union Pacific Railroad (UP) through Cheyenne, Wyoming from Omaha, Nebraska, 100 miles to the north. David Halliday Moffat, one of Denver’s most important financiers and industrialists, had a vision. Having built several rail lines for a few railroads such as the Denver Pacific Railway (DP) and the Denver, South Park, and Pacific Railway (DSP&P), he wanted to connect Denver and Salt Lake City, Utah by rail. However, David had a problem: the Rocky Mountains were in the way.

By 1887, Moffat was elected president of the Denver & Rio Grande (D&RG), which built a route from Pueblo to Grand Junction via Tennessee Pass. Beginning in 1902, David Moffat and his associates established the Denver, Northwestern & Pacific Railway (DNW&P) to address the issue of Denver having been bypassed by both the UP in Cheyenne and the D&RG in Pueblo.

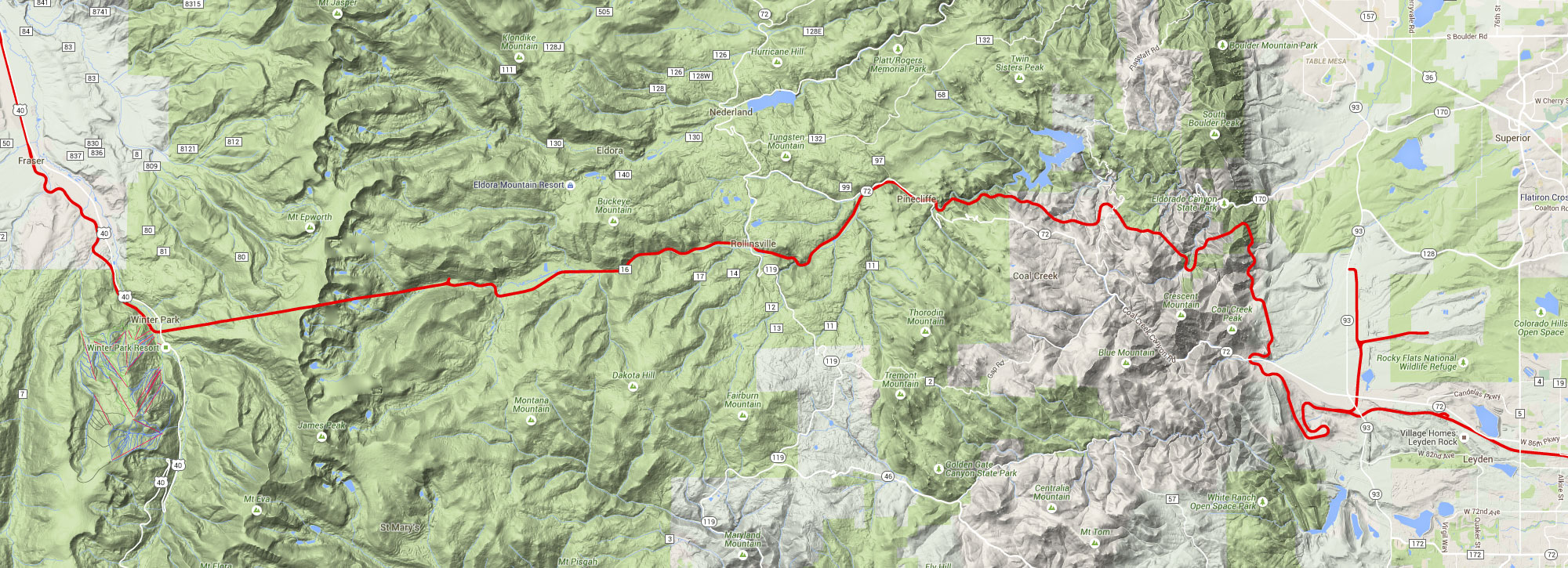

Moffat began construction of the route west out of Denver on December 18, 1902. The railroad had to gain over 4,000 feet in just 50 miles with a grade of no more than 2%, a challenge for Chief Engineer H.A. Sumner. He laid out a very efficient route to gain such altitude, parts of which are still used today, such as the Big Ten Curve. Following the Front Range Foothills, the line snaked west just south of Boulder, near Eldorado Springs. To reach the village of Tolland, 40 miles west of Denver, 33 tunnels were bored. However, the struggles of building the line west were not over yet.

After reaching a point west of Tolland by 1903, the route had to be built over Rollins Pass, at an elevation of 11,680 ft, making it the highest railroad in North America, with grades up to 4%. By the winter of 1904, the railroad reached Arrow. In 1905, the rail line was completed to the town of Fraser down the grade on the west end. From there, the route continued west through small towns such as Tabernash, Granby, and onto Kremmling by 1906. The railroad continued west through scenic Gore Canyon on towards State Bridge. From there, the line went northwest and eventually reached the town of Steamboat Springs by the winter of 1909.

David Moffat passed away on March 18, 1911 at the age of 73 in the state of New York. The DNW&P was placed into receivership on May 2nd, 1912, and on April 30, 1913, the railroad was reformed as the Denver & Salt Lake Railway (D&SL); the railroad did go bankrupt before reaching Salt Lake City. By the year 1913, the tracks from Steamboat Springs reached Craig, Colorado, the terminus for the D&SL. The route was only half the distance to Salt Lake City, and the D&NWP had cost Moffat $75,000 a mile and Rollins Pass his entire fortune, for a total of $14 million.

Severe winters plagued Rollins Pass over the years, causing many closures. Since the railroad could not handle the harsh winters, the construction of a tunnel underneath the continental divide was started. Construction of the tunnel began in 1923 and was completed in 1927 by the D&SL. The 6.2-mile long tunnel reached its “apex” at an elevation of 9,239 ft, and the route through the Moffat Tunnel had cut the travel distance by 16.8 miles.

The Denver & Salt Lake Railroad was recognized as the Denver & Salt Lake Railway in 1926. By 1931, the Denver & Rio Grande Western Railroad acquired the Denver & Salt Lake Western Railroad, a subsidiary of the D&SL, which had gained rights to build a 40-mile rail line connection between the two railroads, and the D&RGW gained trackage rights between Denver and the new cutoff. In 1932, the D&RGW began construction of a connection east of Glenwood Springs at Dotsero to a location near Bond called Orestod (Dotsero spelled backwards). The Dotsero Cutoff completed the east-west connection between Denver and Salt Lake City. In 1947, the D&SL was absorbed into the D&RGW, which gave the railroad access from Denver to Craig.

Plainview

Even though David Moffat was known as a vain dreamer, his determination has created a legacy that would live on with the D&RGW and to the present on the UP. Today, the same railroad is used as the Central Corridor connecting Denver to Craig and Salt Lake City.

Operations

Since the climb up to the continental divide from Denver is mostly a constant 2% grade, westbound trains usually get a good workout for about 35 miles to the East Portal. Empty coal trains heading back to the mines in western and northwestern Colorado usually operate in a 2×1 power configuration, with all three locomotives online just to get up the grade. Westbound manifest trains from the UP generally run in a 3×1 configuration, depending on tonnage. BNSF’s westbound trackage rights manifest to Provo, Utah usually runs anywhere from 3×0 to 3×2.

Radio Frequency –

- Denver – Rocky: 160.320

- Rocky – East Portal: 160.455

- Winter Park – Bond: 160.920

- Bond – Phippsburg: 160.320

- Moffat Tunnel: 161.565

Train Symbols –

Union Pacific:

Manifests: MNYRO, MRONY, MNYPH, MPHNY, MNYGJ, MGJNY

Coal Trains: CEYPS, CPSEY, CEYVL, CVLEY, CEYCM, CCMEY, CEYKH, CKHEY, CWECC, CCCWE, CWEAO, CAOWE, CWEHM, CHMWE, CWEMS, CMSWE, CWEDH, CDHWE

*All coal trains are not daily and expect to see probably two to four coal trains on any given day.

Oil Trains: OPWKN, OKNPW

*Oil symbols can also change and vary at times.

BNSF Railway:

H DENPVO / QDVPVJ (BNSF symbol / UP symbol), H PVODEN / QPVDVJ (BNSF symbol / UP symbol)

*Some BNSF trains can either run as the QDVPVJ or QLIPVJ and vice-versa.

Eastbounds climbing the hill on the west end usually encounter a 1-1.5% grade, but most still get a decent workout. Loaded coal trains will have six locomotives, usually in a 2x3x1 configuration. The three distributed power units (DPU’s) in the middle act as swing helpers that are later removed in Denver. On some occasions, loaded coal trains, such as the Valmont train, run in a 2x2x2 configuration so the train can be handed over to the BNSF and travel north over the Front Range Subdivision to the Valmont Xcel Energy Power Plant in Boulder, Colo. UP manifest trains generally run in a similar configuration as their westbound counterpart. The BNSF trackage rights manifest from Provo however, usually does not require DPU’s and runs in a 3×0 configuration.

Tolland

Over the years, the downfall of coal business has put a damper on train traffic over the Moffat Route. Only two coal mines remain open: the Energy Mine on the Craig Branch and the West Elk Mine on the North Fork Branch (south of Grand Junction, Colo.). The majority of the coal traffic goes to two power plants in Colorado, while the rest heads east to Illinois, Kentucky, Tennessee and Mississippi, and south to Texas and Arizona.

Other traffic that runs over the Moffat Route includes Amtrak’s California Zephyr trains running between Chicago, Ill. and Emeryville, Cali., and crude oil trains from Wash, Utah to points south and east.

Locations

Eisele

Denver – Rocky:

Denver is the starting point for the Moffat Tunnel Subdivision, with Union Station as MP 0.0. All of the Moffat traffic for all three railroads must pass by or through UP’s North Yard, about three miles north of downtown. Most UP coal trains do not require to go into North Yard unless power is being swapped, added or taken off. The coal trains change crews on two bypass tracks that connect the Moffat Tunnel Subdivision with the Belt Line Connection with UP’s 36th Street Yard, Greeley Subdivision, and Limon Subdivision north of Pullman Junction. The majority of the coal traffic departs and arrives on the former Kansas Pacific route from Kansas City at Pullman Junction.

Heading west, the tracks arrive at C&S Junction. This is the point where BNSF’s Golden Subdivision to Golden splits off from the UP. The tracks continue west and northwest through the Denver suburb of Arvada until they reach the first passing siding on the subdivision, a 7,020-ft siding called Leyden. The siding is frequently used for meets and is also a good holding point for trains that cannot go straight into Denver.

As trains continue west, they immediately hit the 2% grade leaving Leyden. Colorado Highway 72 joins up with the tracks at the west end of the siding and follows the tracks for a couple of miles to a location called Chemical. One can get some wide-angle shots near the overpass at the west end of Leyden, from the highway to the intermediate signals at Chemical. On most days, one can get a westbound climbing the grade into Chemical with the Denver skyline in the background.

For the next couple of miles, both the tracks and highway 72 split off. Highway 72 then meets up with Highway 93 from Golden and Boulder. The tracks exit Barber’s Gulch and duck under highway 93 just south of the highway 72/93 intersection. From there, the tracks curve and enter the next passing siding called Rocky. This is the point where trains change radio channels and dispatchers. Unfortunately, the siding at Rocky is not accessible to the public.

Big Ten Curve

Rocky – Pinecliffe:

Between Rocky and Pinecliffe, westbound trains continue to climb up a constant 2% grade. In the 20 miles between Rocky and Pinecliffe, trains gain about 2,700 ft in elevation. This is all possible thanks to a 2% grade, 29 tunnels and Big Ten Curve. However, between Rocky and Plainview, the railroad had to gain 600 ft in elevation without exceeding a 2% gradient. Big Ten Curve made the travel distance to seven miles rather than two miles, but kept the grade at 2% rather than 4%. Westbound trains depart Rocky and immediately start up the 2% grade before wrapping around a 190 degree horseshoe curve and reaching the next passing siding called Eisele. Rocky, Big Ten Curve, and Eisele can be accessed on foot by hiking a couple of miles in the Jefferson County Open Space south of highway 72.

After departing Eisele, trains enter the eastern rim of Coal Creek Canyon. The tracks cross over Blue Mountain Road at a grade crossing and highway 72 on an overpass before climbing the grade and reaching tunnel 1 and the next passing siding at Plainview. Most of Coal Creek Canyon is located in the Jefferson County Open Space. From the intersection of highway 72 and 93, head west and enter the eastern rim of the canyon. Before passing underneath the tracks, you come up to two roads: Plainview Road to Plainview siding or Blue Mountain Road, which leads up to the grade crossing and overlook above Big Ten Curve.

Coal Creek Canyon

Tunnel 1 is the beginning of the so-called “tunnel district”. Between Plainview and Crescent, most of the tunnels are not accessible; most require a lot of hiking and some may involve trespassing on private property. Continuing west from Coal Creek Canyon, take highway 72 for several miles before coming to Crescent Park Drive. In order to access Crescent, turn off at Crescent Park Drive and head north for about a half a mile before coming up to Gross Dam Road. Make a right and head north and east for about a mile before meeting up with the tracks at a grade crossing. Here, one can get eastbounds with the continental divide in the background.

From Gross Dam Road, one can also access tunnel 19. When taking Crescent Park Drive from highway 72, you drive about a half a mile before reaching a point in the road where you either head west and get back onto highway 72 or continue east then north to the grade crossing at Crescent. Tunnel 19 is just west of Crescent and can be accessed by some driving and a little hiking. In order to get to tunnel 19, take Crescent Dam Drive from highway 72 and head north before you reach the fork in the road a half a mile north. Make a left onto Gross Dam Road and another half a mile before coming to Tunnel 19 Road. Make a right and head north for about three quarters of a mile before coming to a dead end. There is enough room to park your vehicle there. At that point, you are standing above the tunnel, but to access the east portal, you have to hike east-northeast for about a quarter of a mile. The same thing goes for the west portal, but head west-southwest. For the next five miles, the tracks pass through ten more tunnels along South Boulder Creek before entering the small unincorporated community of Pinecliffe.

Tolland

At Pinecliffe, highway 72 rejoins the tracks at a grade crossing near the east end of the siding, not far from the post office. Before entering Pinecliffe, highway 72 passes an overlook right above the tracks and South Boulder Creek. There is a pull off, so parking is easy. From here, one can hike up on a rock and look over the tracks and South Boulder Creek.

Pinecliffe – East Portal:

Between Pinecliffe and East Portal, the tracks snake along South Boulder Creek away from highway 72 and pass by Pactolus Lake. At one time, Pactolus was used to make ice that the railroad carried in boxcars. The tracks then enter the small village of Rollinsville, where highway 119 from Boulder and Black Hawk cross the tracks on an overpass. Just before the overpass, East Portal Road heads west and pretty much follows the tracks all the way to the Moffat Tunnel. Just west of Rollinsville, the tracks, South Boulder Creek, and East Portal Road snake their way through a small canyon that offers beautiful scenery. After the tracks cross South Boulder Creek, the road and tracks enter a small valley before entering the small unincorporated village of Tolland. Tolland only consists of a few houses, the county sheriff office, and a 9,356-ft passing siding.

Pinecliff

For the next three miles, the road and tracks head through the western edge of the valley at Tolland before crossing South Boulder Creek one last time. East Portal Road crosses underneath the tracks at a small overpass on a sweeping s-curve. From there the road parallels the creek and tracks before coming to a grade crossing at the east end of East Portal siding. About a half a mile from the grade crossing, East Portal Road joins up with what was once the original right-of-way over Rollins Pass. Continue west until you reach a parking lot used for hikers and railfans and the Moffat Tunnel. Signs warn people to stay away from the tunnel, and surveillance cameras monitored from UP’s Harriman Dispatch Center in Omaha keep eyes on the tunnel in both a west and east direction. However, with a telephoto lens, one can still get good shots of trains entering and exiting the Moffat Tunnel.

More of John Crisanti’s work can be found here: www.flickr.com/photos/john_crisanti_photography

About the Author

John Crisanti is a 22 year old railroad photographer that resides in Longmont, Colorado along BNSF’s Front Range Subdivision between Denver, Colorado and Cheyenne, Wyoming. The interest of railroads came at a young age when his father would always take him trackside just to watch the trains go by. He also adapted the interested in photography from his father as well, who has had previous experience being a freelance photographer for a newspaper firm years ago. For the past several years, John has developed an interest in railroad photography with inspirations from known railroad photographers such as the Danneman brothers. His favorite rail line to photograph trains is the Moffat Route as it offers some of the best scenery in the country right in his own backyard.

Like and Share with your friends and family!

Tomas

Dear Mr.Crisanti,

I am writing little artcile about Moffat’s tunnels. Especially about tunnel n.30.

http://clairewindsor.weebly.com/uploads/2/4/5/9/24594201/7457706_orig.jpg

Unfortunately I can’t find any information about this “special” tunnel. So let me ask you for little help. Please if you have any information about tunnel n.30 and if you want. Please help me.

Yours sincerely.

TV

Tristan

@Tomas, that’s the east portal of tunnel #29 — either mislabeled as #30 or the numbering was different back then.

Todd Taylor

Great Information!

Marshall Myrick

Really nice work on the history. The maps are very useful, and your photography is outstanding!

Hanna

Thank you for the journey !! It was fascinating.

Joyce

Loved reading about the history of the railway. Your information was beautifully written, it held my attention the whole journey. Thank you Joyce Patterson